LIVERPOOL SHIPS

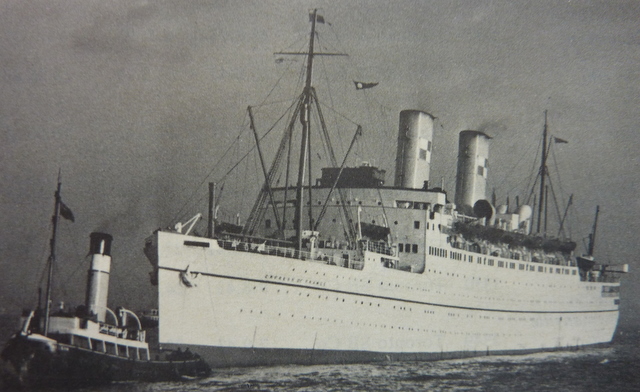

THE CANADIAN PACIFIC LINER 'EMPRESS OF FRANCE' (ex 'DUCHESS OF BEDFORD') of 1928

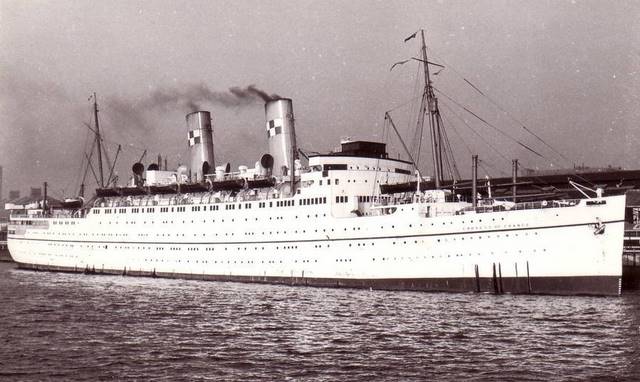

Built by John Brown & Co. Ltd. at Clydebank in 1928 Yard No: 518 Official Number: 160482 Signal Letters: G N T V Gross Tonnage: 20,448 Nett: 11,335 Length: 581.9 feet Breadth: 75.2 feet Owned by the Canadian Pacific Railway Co. (Canadian Pacific Steamships - Managers) 6 steam turbines, single reduction gearing to twin screws. Speed: 17.5 knots

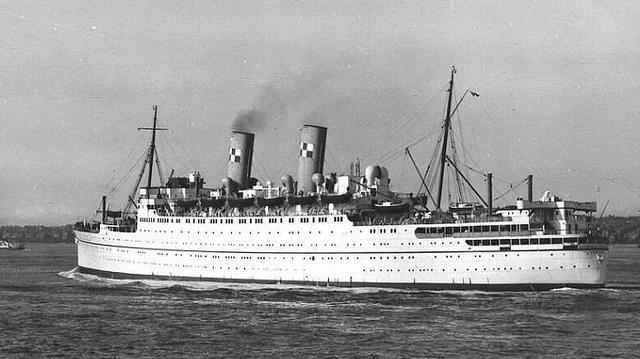

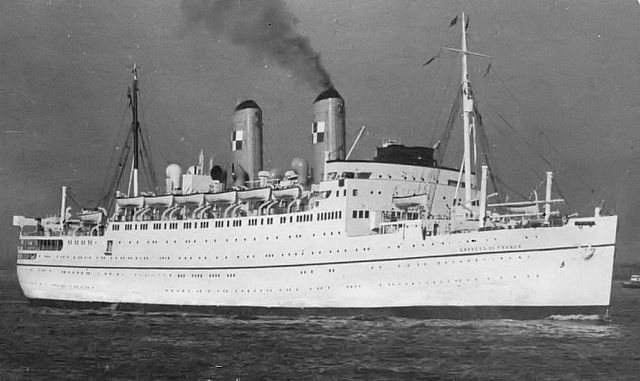

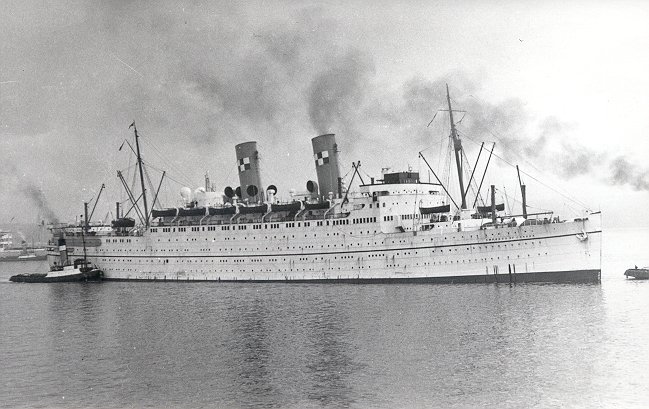

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE steaming up the Mersey in 1949

The DUCHESS OF BEDFORD took the concept of the 'cabin-class' ship to its highest point. She was one of four sisters, the others being the Duchesses of Atholl, Richmond and York.

The DUCHESS OF ATHOLL was intended to be the first in service, but an accident involving one of her turbines when she was fitting out meant that this honour fell to the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD, whose completion was speeded up so that she could take the first sailing on the advertised date of 1st June, 1928.

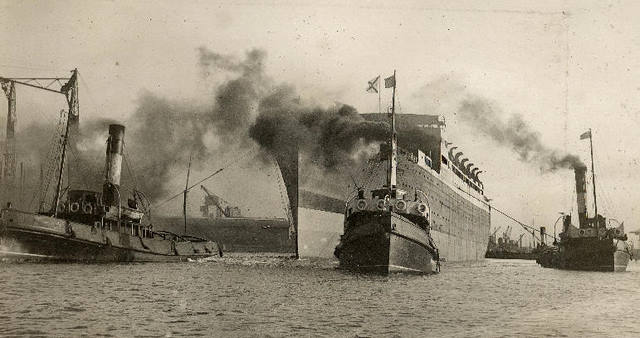

The DUCHESS OF BEDFORD on the occasion of her maiden voyage from Liverpool on 1st June 1928. After extensive service in the Second World War, the ship returned to commercial service in September 1947 as the EMPRESS OF FRANCE.

The DUCHESS OF BEDFORD was launched on 24th January 1928 by Mrs Stanley Baldwin, wife of the then prime minister. The new liner had a deadweight capacity of 8,750 tons, which included 2,725 tons of fuel oil, and she could very easily exceed her designed speed of 17.5 knots. Her original accommodation was for 580 in cabin class, 480 in tourist class and 510 in third class. A crew of 510 was carried.

The launch of the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD from John Brown's Yard at Clydebank on 24th January, 1928.

On her second westbound voyage the Duchess established a new record for the passage between Liverpool and Montreal of six days, nine and a half hours, saving almost a full day on the previous best. Although she was only intended to make 17.5 knots, she could average 18 knots without the least difficulty, and could steam at 20 knots for considerable periods.

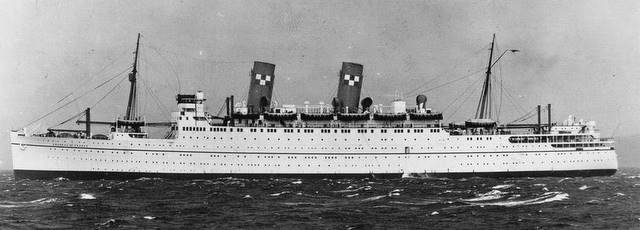

The DUCHESS OF BEDFORD on her trials - she had a maximum speed of 20 knots

At the beginning of 1933 the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD was on charter to Furness Withy & Co, and sailed on the New York - Bermuda service whilst the QUEEN OF BERMUDA was being completed. On 8th May 1933 the Duchess was the subject of an absolutely unfounded rumour that she had sunk after striking an iceberg off the Newfoundland coast with passengers and about £5000,000 of gold bullion on board. The distress that this must have caused to the relatives of those on board was not alleviated until 2.am the following day when the liner radioed from mid-ocean that all was well with her.

Two months later, on 13th July 1933, the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD actually did strike an iceberg in the Belle Isle Strait between Newfoundland and Labrador, but fortunately was undamaged, and six years later, in June 1939, she brought thirty-two Frenchmen whose barquentine had sunk after striking a berg off Newfoundland, safely to Liverpool.

On the outbreak of the Second World War the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD was requisitioned for service as a troopship for which she was admirably suited by her original design. Just before the fall of Singapore in January 1942 she arrived with 4,000 Indian troops and 40 nurses. Packed with refugees, including 875 women and children, she got away five days before the surrender. Later in 1942 the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD arrived at Liverpool with the first US troops: 673 officers and 6,507 men. She was given the credit for sinking a U-boat about this time, and the Duchess ended a very eventful year stranded during the French North African operations. The Irish Sea packets ULSTER MONARCH and ROYAL ULSTERMAN had to tow her free.

After North Africa came the Sicilian and Italian operations. In 1943 the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD was the first transport in at the Salerno landings. In the Spring of 1945 she carried to Odessa a large number of Russian prisoners who had been liberated by the Allied advance in Europe, and returned with Allied prisoners whom the Russians had rescued. Considering the extent and variety of her war work, covering some 350,000 miles and carrying 231,000 troops, it was remarkable that the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD escaped any damage, although she had very many narrow escapes.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE as she appeared after her post-war refit

After the War the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD was employed in repatriating troops, service wives and children to Canada, and she arrived at the Fairfield Yard at Govan to be reconditioned in 1947. She was renamed EMPRESS OF FRANCE (although the original intention was to rename her EMPRESS OF INDIA), and her accommodation was rebuilt to carry a total of 400 passengers in first class and 300 in tourist class.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE alongside her berth in Gladstone Dock, Liverpool in the Canadian Pacific North Atlantic post-war colours.

The machinery was thoroughly overhauled, new propellers were fitted, and she was painted in Canadian Pacific's new Atlantic colours of white hull with green riband and boot-topping, with buff funnels having the Company's houseflag painted on either side. The EMPRESS OF FRANCE returned to the Liverpool - Montreal service on 1st September 1948.

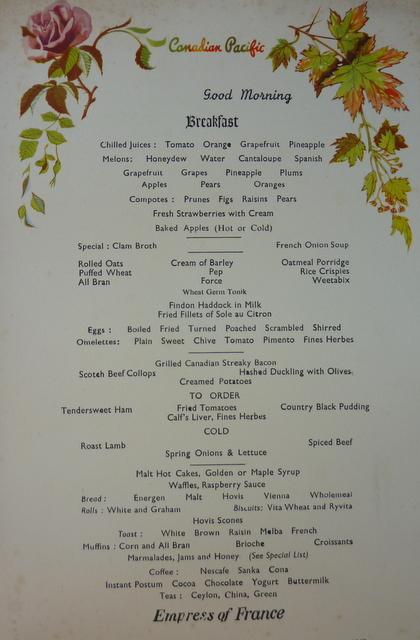

Good Morning : the first-class breakfast menu on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE

The first-class lounge on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE

The first-class cocktail bar on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE

The first-class Long Gallery on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE, connecting the public rooms.

The first-class card room on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE

The tourist-class restaurant on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE

A two-berth tourist-class cabin on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE

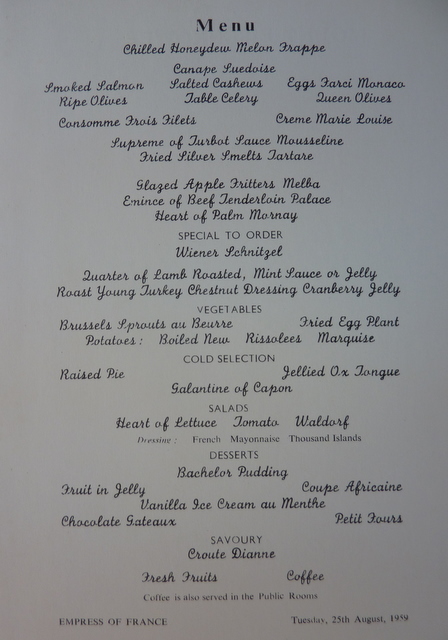

The tourist-class dinner menu on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE on 25th August, 1959

It was intended that Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh would sail to Canada at the start of their 1951 tour on board the EMPRESS OF FRANCE, but the King's illness forced these arrangements to be cancelled, and the royal couple went by air. However, Captain Ben Grant, master of the EMPRESS OF FRANCE, was not forgotten and he was invited to a reception at London's Guildhall where he met the royal couple on their return from Canada on board the EMPRESS OF SCOTLAND.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

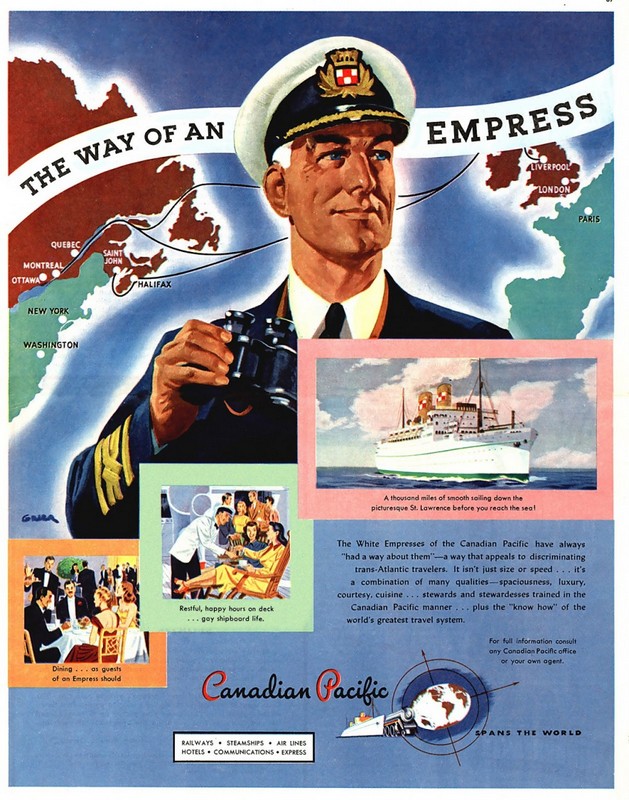

COMPANY PILOT The Canadian Pacific funnel colours, house-flag and distinctive names made its ships some of the most recognisable in Liverpool. Along with many other companies, Canadian Pacific retained the services of its own chosen Liverpool pilots by appropriation, but on one occasion neither of the comany's two pilots was available and the EMPRESS OF FRANCE was obliged to engage a pilot from the general rota list. On reaching the bridge of the White Empress, Pilot Gordon Williams, a highly experienced man,was greeted by a master who was clearly less than happy at having a stranger on board. In somewhat superior tones the master demanded to know: "Have you ever piloted a ship of this company before?", to which Pilot Williams replied: "I'm not sure, Captain. Which company does she belong to?"!!.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

During her refit in 1958, the EMPRESS OF FRANCE was given what was claimed to be a more 'modern' appearance. This involved two new tapered funnels with raked tops. This did not particularly suit her and many of her admirers felt that her profile had been ruined.

The new forward 'modern' funnel on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE It was the opinion of many people that her profile had been ruined.

Those unfortunate 1958 'modern' funnels!

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE lasted until 1960, making her last voyage in October of that year. On Monday 19th December she left Liverpool under her own steam for Newport, Monmouthshire, where she was broken up by John Cashmore & Sons. It was a time of sad 'farewells' on the Mersey, for just three days previously the BRITANNIC had left Liverpool, also for the breakers' yard.

Finished with Engines Chief Engineer John Parkes and Second Engineer Leslie McGowan check the final entries in the log book after the EMPRESS OF FRANCE's final voyage on 29th October 1960.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE leaving Gladstone River Entrance at Liverpool on 19th December 1960, bound for the breakers' yard.

________________________________________________________________

LATE FOR HIS OWN FUNERAL - LITERALLY!

by Ted Morris

In the run-up to Christmas 1948, I was serving as Fourth Officer in the EMPRESS OF FRANCE. Shipment of mail that year was particularly heavy and stowage in the secure lockers became problematical as the time for sailing from Liverpool approached. The safe carriage of the mails and any 'special' parcels and items was my responsibility, and I had also accepted a crated coffin, containing the remains of a gentleman and destined for discharge at Quebec, and which was now resting in the specials locker.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE in the Mersey

Within the limits of practicability we always afforded such situations the utmost reverence but on this particular occasion a late arrival of mail for Montreal left me no choice of stowage space other than the said locker. The mail was duly loaded but because of the excessive number of bags, the crate in question was very unfortunately overstowed.

I was sometimes fascinated by various remarks made and questions asked by relatives of deceased persons whose remains were travelling with us. They seemed to have the impression that the casket would be serenely mounted on a catafalque with the traditional candles at head and foot or, perhaps,armed guards at the four corners, resting on their reversed arms! Not so, I fear, but I had to be happy with the existing situation and console myself that there was no real breach of ethics.

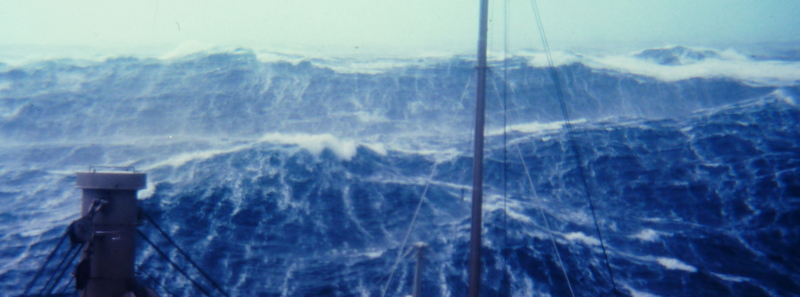

A turbulent westbound passage

A turbulent westbound passage caused a late arrival at Wolfe's Cove, Quebec, and an ultra-fast disembarkation of passengers and discharges of ancillaries. Air temperatures were falling and this was definitely the last voyage of the season and everything was hurry, hurry, hurry.

Air temperatures were falling and this was definitely the last voyage of the season as winter set in on the St Lawrence at Quebec

In quick time we were off the berth and heading up river at best speed on our way to Montreal, more than satisfied with ourselves, but imagine the scene as my particular complacency was shattered when the Staff Captain informed me (in dulcet tones, of course!) that a message had been received from Quebec that a BODY had gone missing, and that funeral directors had called for collection - in vain!

The situation was awesome, and now ethics were fighting economics in my mind. All sorts of reasons and excuses relative to our quick staf in Quebec could be given, but the facts could neither be denied nor forgiven. The remains of my deceased must now stay with us to Montreal, and then be transported back to Quebec by some means or another.

Distress to relatives would be inevitable, not to mention the obvious enormous expense involved and the awful fact that, as mentioned in the title of this anecdote, the gentleman in question really had missed his own funeral!

This must be the nearest I ever came to a 'Decline to Report' - I think !

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE passing under the Jacques Cartier Bridge on arrival at Montreal

_______________________________________________________

LIFE ON THE 'EMPRESS OF FRANCE' IN 1949

by Captain J.C. Moffatt

I joined the EMPRESS OF FRANCE as fifth officer in Gladstone Dry Dock, Liverpool in November 1949. The ship was undergoing refit, having just completed her first post-war year on North Atlantic service.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE in the Gladstone Dry Dock at Liverpool, undergoing annual overhaul

The taxi driver helped me carry my luggage on board and I reported to the chief officer. He welcomed me on board and showed me to my cabin which was small but well-appointed: a bunk, settee, desk, wardrobe and a washbasin with hot and cold running water. A far cry from the old compactum-type washbasin in my last ship, the CLAN MACNEIL.

I was introduced to the first and third officers who were standing by the ship. Although we were sleeping on board there was no victualling and we were paid seven shillings a day to feed ourselves. The chief officer then told me that he was about to cook a light meal for the stand-by officers, probably beans on toast. At the time I thought it was a bit strange as I had never known a chief officer to do the cooking before !

After unpacking I went on ship rounds with the third officer. Being new to passenger liners I soon realised that I was lucky to join the ship in refit as I quickly got to know my way around. On my first morning aboard I joined the others in the wardroom where the chief officer (who held an extra master's certificate) dished up a superb breakfast of porridge, boiled eggs, toast and marmalade. "I don't suppose you have experienced this arrangement before, have you?" he asked me. He then went on to explain that we had a steward in the daytime to make our bunks, clean our rooms, the wardroom and to wash up the dishes. The rest of the time we looked after ourselves. I was also informed that it was my job as the most junior officer to go to the local grocery store in Seaforth every Friday armed with cash, grip-bag, ration cards and a list of groceries to be purchased for the wardroom.

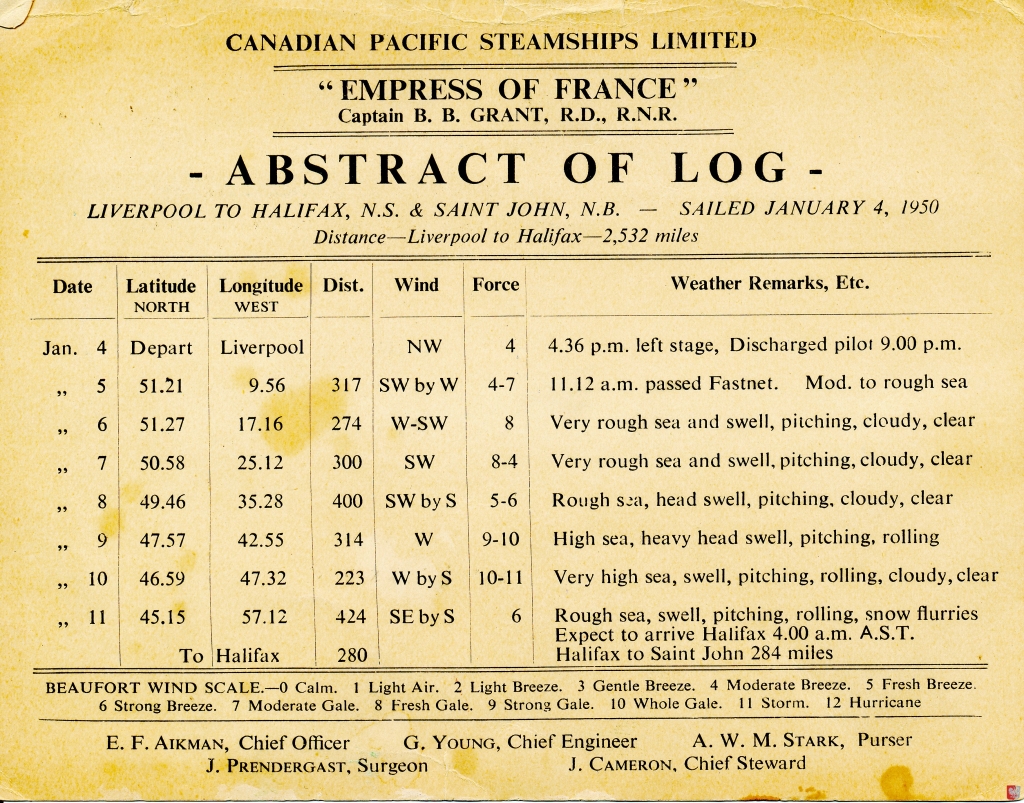

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE left the dry dock on 29th December 1949. The chief officer took me to meet the captain. I was shaking in my shoes. On being being introduced I was immediately made to feel at ease and was welcomed to the ship.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE alongside her berth in No.2 Gladstone Branch Dock, Liverpool

The atmosphere on board was friendly and after six weeks I had settled into harbour routine. After leaving the dry dock we secured in No.2 branch Gladstone Dock to commence loading. Ship's Articles were opened on 2nd January 1950 and the next day we commenced to feed on board. The food was very good and there was plenty of it.

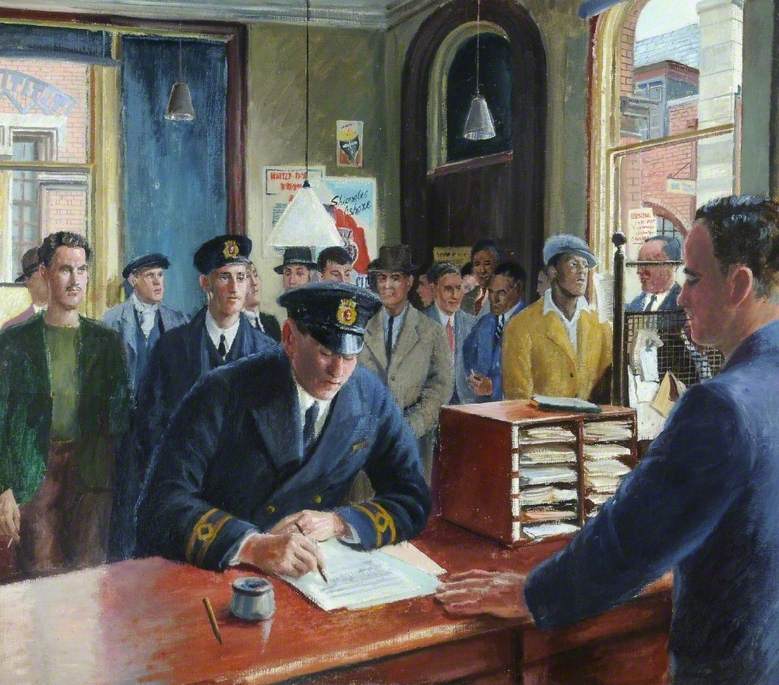

Signing on the ship's Articles of Agreement before the Shipping Master at the Mercantile Marine Office

The ship now had a full complement of officers: Master, six deck, four radio, four pursers, twenty plus engineers (including electrical and sanitary engineers), chief and second stewards, a Canadian rail traffic officer and a nursing officer.

Fire and lifeboat drills including an 'abandon ship' exercise were carried out under the eagle eye of the B.O.T. Surveyor and the ship was granted her Safety Certificate. Over the next ten days the Empress was stored and general cargo loaded. Twenty-four hours before departure hundreds of bags of mail arrived. The EMPRESS OF FRANCE alongside Princes Landing Stage, Liverpool

On Tuesday 10th January 1950 we left Gladstone Dock at 10.am and were secured alongside Princes Landing Stage by 11.30. The ship was gleaming and stewards were buzzing about in preparation for the embarkation of 600 passengers. The junior officers were on gangway duty throughout the period of embarkation. At 1.pm I went down to the first-class dining saloon for lunch and experienced my first meal dining from the first-class menu. I thought to myself: "I am going to enjoy life in this ship!"

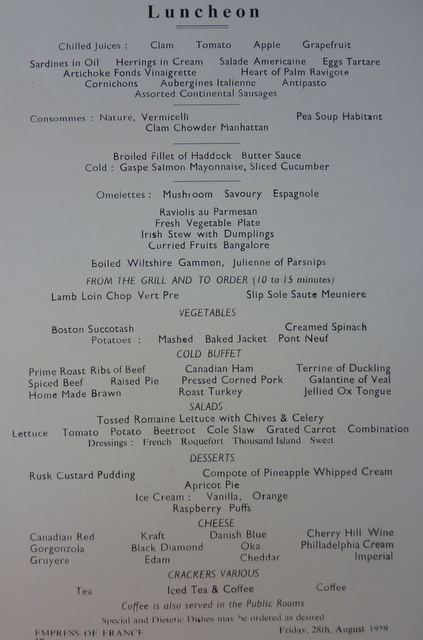

Luncheon in the first-class dining saloon on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE impressed Captain Moffatt !

Embarkation was completed by 4.pm and half-an-hour later we sailed for Halifax, Nova Scotia, and St John, New Brunswick.

I was to keep watch with the second officer on the 12 to 4. After dinner I turned in at 8.30pm to get some sleep before I was called at a quarter to midnight. I spent most of my first watch on the bridge wing as the EMPRESS OF FRANCE proceeded down the St George's Channel. It was a bitterly cold night. Visibility was excellent and there was a large number of ships proceeding towards Liverpool and Glasgow. My senior on the watch was very good, giving me much valuable advice both on the working side and what was expected of one socially on an Empress at sea.

The watch passed quickly and at 4.am we handed over to the first and fourth officers. The second officer had informed me earlier that the 12 to 4 watch was not required to do a breakfast relief and that I could stay in my bunk until 10.am. I thought he was joking and just smiled. I turned in at 4.20am and was somewhat surprised when the steward called me at 10.am with a breakfast tray. He said: "You hadn't left any instructions, sir. Therefore I thought it would be a good idea to call you at the same time as the second." This was definitely a different type of life from cargo ships !

Typical North Atlantic winter conditions

As we steamed west the weather started to deteriorate and forty-eight hours after leaving Liverpool we were pitching heavily into a head sea. Twenty-four hours later the temperature started to drop and it continued to do so as we approached the Grand Banks. Apart from watchkeeping duties at sea, I did not have much extra work. I was responsible to the chief officer for the upkeep of stationeery and all signalling equipment.

Social life at sea was good. Junior officers were not allowed in the public rooms, except on cinema night, but were expected to entertain passengers during morning coffee and afternoon tea.

Two nights before arrival at Halifax was 'Gala Night'. That was the night of the voyage, with extra special dressing up. The orchestra played in the dining room and the menu was out of this world.

On Monday 18th January we passed Chebucto Head and entered Halifax harbour. It was bitterly cold; in fact I had never felt so cold in all my life. I realised that I would have to get some extra gear as soon as we arrived in St John. We were alongside at Halifax for five hours and a number of passengers disembarked and transferred to the Canadian Pacific Railway for the final part of their journeys to the Canadian interior.

With mail and baggage discharged and water tanks topped up, we sailed at 1.pm. When we secured alongside our berth at St John the next day, the snow was at least a foot deep. During passenger disembarkation the fourth officer and myself did gangway duty. By noon the passengers had all gone and we commenced harbour routine. Along with the third and fourth officers I was required to do twelve hours on and twenty-four hours off.

Throughout our stay at St John we worked cargo and tended moorings (the tidal range was over 20 feet). Over the weekend large numbers of local people came down to the docks to see the 'White Empress' - it was always a great occasion when we docked at St John.

On 24th January 1950 we embarked our eastbound passengers, completed loading cargo, baggage and mail. bunkering and topping up of water tanks, and at noon we sailed for Halifax and Liverpool. The weather was foul on the passage home, and we were six hours late arriving at Liverpool. I enjoyed my time on the EMPRESS OF FRANCE, and I was very sorry some months later when I was transferred to another ship of the line. <<<<<<<>>>>>>>

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE arriving off Gladstone River Entrance. Note Alexandra Towing's FLYING BREEZE on the right.

______________________________________________________________________

PROUD SHIP ON THE MERSEY - CANADA RUN

by a 'Liverpool Echo' reporter, April, 1958

Walk on board the Canadian Pacific liner EMPRESS OF FRANCE in Gladstone Dock and it will seem strangely quiet. It is the day before sailing and the lounges and cocktail bars are deserted in marked contrast to the gay scenes there when the ship is at sea.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE alongside the Princes Landing Stage, Liverpool. left to right: Cunard Line's SAMARIA, the ROYAL IRIS, the EMPRESS OF FRANCE and the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company's KING ORRY.

But do not be misled by the quietness. Without any fuss the staff on board are diligently attending to their duties. Two orderly queues are formed up on one of the decks. This is 'signing-on' day and the crew are presenting their discharge books to the shipping master and company officials before signing the ship's Articles of Agreement.

As dockside cranes lower cargo into the holds, sixty-two-year-old Patrick McAleavey, first-class cocktail bar steward from Blundellsands, puts a few finishing touches to the already mirror-clean fittings and furniture. He's been with Canadian Pacific for forty years and has probably served enough cocktails to float the Empress.

First Officer John Walker of Great Crosby checks over documents on his cabin. They show that the EMPRESS OF FRANCE brought in 2,100 tons of cargo, 70 first-class passengers and 370 tourist-class passengers on her last eastbound voyage. And now for the forthcoming voyage the ship is loading 1,000 tons of exports. The last of the consignment of 'Hot Rod' racing cars for the Canadian market is lifted from the quay and gently lowered into the forward hold. Inside the dock shed, lorries are still being loaded with the inward cargo from Montreal.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE alongside the Canadian Pacific berth at Montreal.

In the first-class dining saloon Arthur Wilson of Wallasey notes that there will be 601 passengers on the outward trip, and that 127 are travelling first class. He'll spare a moment to tell you that he first joined the EMPRESS OF FRANCE in 1936 and has sailed with her on every voyage except one. Arthur will tell you that when the ship (then the DUCHESS OF BEDFORD) made her first voyage of the war to Bombay, she had a skirmish with submarines. On another voyage, from Liverpool to Boston, the ship was credited with sinking one U-boat and badly damaging another. The damage to the enemy was done using a First World War vintage gun mounted on the stern.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE is indeed a proud ship with a proud record. If time permits, Arthur Wilson will describe the occasion when the Empress was the last ship to leave Singapore after the capitulation. But she did not escape without damage from Japanese shrapnel bombs. Arthur was there when the ship took part in three invasions - North Africa, Salerno and Anzio. She was carrying American commandos to Salerno and was HQ ship under the command of Captain 'Pony' Moore. The American commander of the invading force was so pleased that he ordered 'splice the mainbrace' !

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE alongside the landing stage at Liverpool

Not one man was lost during the ship's wartime trooping career. She steamed 322,543 miles and carried 149,166 personnel. The Empress was lucky the night she dropped anchor in the Mersey during the ten-day Blitz on Liverpool in May 1941. Bombs rained down and the ship was one of the special targets. As the EMPRESS OF FRANCE was swinging with the tide a stick of bombs fell near her starboard side, but she escaped damage. The next morning the ship was ordered to the Clyde.

Chief pastrycook is Thomas Patten of Plymouth, aged fifty-four, who first went to sea in 1924 after learning his trade ashore. He recalls one occasion when he made a cake 4ft x 2.5ft x 1ft high. It was in the form of a football pitch, complete with players This was in 1937 when the famous amateur champions, Islington Corinthians, travelled in the ship. Everyone on board received a piece of the cake as a memento.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE at Liverpool towards the end of her Canadian Pacific career, sporting her 'modern' funnels

A man with a lot of responsibility on board the EMPRESS OF FRANCE is Thomas Mercer who lives near Chester. He's the chief steward and has been with Canadian Pacific for twenty-seven years.

The EMPRESS OF FRANCE has a happy crew, many of whom have had the opportunity of moving on to other ships, but who have preferred to remain with 'the last of the four Duchesses'. Her master is Captain John Soame who says: "I am very proud to sail in the EMPRESS OF FRANCE. She is a fine old ship with plenty of life left in her, and is very popular with passengers and crew."

______________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________ |