LIVERPOOL SHIPS

THE ELDER DEMPSTER LINER 'ACCRA' OF 1947

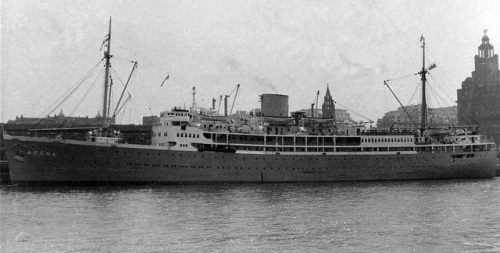

The ACCRA alongside her berth in North Liverpool docks.

At the end of the Second World War, Elder Dempster's mail-boat passenger fleet had been wiped out. Four of the passenger liners were war losses, and on the cessation of hostilities, just the ABA of 1918 remained and was returned to Elder Dempster, but she was not worth reconditioning.

If the passenger service from Liverpool to West Africa was to continue, new ships were an urgent priority, and in February 1945 two new passenger and cargo ships were ordered from Vickers-Armstrong Limited at Barrow-in-Furness. These were the ACCRA and the APAPA, both launched in 1947. These two ships were larger developments of the pre-war Elder Dempster mail liners of the same names. Four years later the graceful AUREOL entered service, remembered by many on Merseyside as the most beautifully proportioned liner ever to use the port.

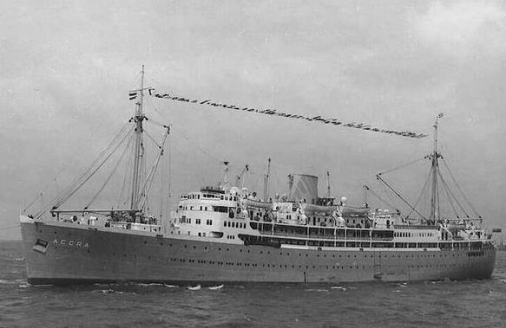

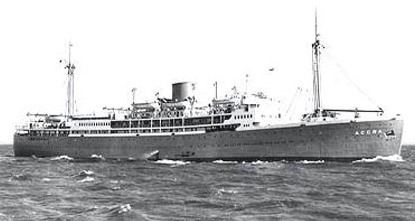

The ACCRA leaving Liverpool on her maiden voyage with the black hull which she carried on her first two years in service

The ACCRA was ordered in February 1945, and was launched at Barrow on 25th February 1947. She left Liverpool on her maiden voyage on 24th September under the command of Captain C.C. Cave. Initially the ship carried a black hull. __________________________________________________________

ACCRA built by Vickers-Armstongs Ltd at Barrow-in-Furness in 1947. Yard No: 948 Official Number: 181100 Signal Letters: G J S W Gross Tonnage: 11,600 Nett: 6,448 Length: 452.9 feet Breadth: 66.2 feet Owned by Elder Dempster Lines, Limited 2 Doxford diesel engines, twin screws. Speed: 15 knots

________________________________________________________________________________

Just over two years later, in November 1949, the ACCRA suffered a broken crankshaft, and she arrived back in Liverpool on one engine, five days late. She was returned to her builders at Barrow for repairs, and during this priod she was repainted in the familiar grey hull and green boot-topping. In 1960 much needed air-conditioning was installed in the passenger decks.

Somewhat unusually, the ACCRA was caught up in strike action by seventy-five Nigerian members of her crew in June 1959. They had been staging a sit-in, alleging racial discrimination, and walked off the ship on 25th June, just twenty-four hours before sailing time. They were classed as 'deserters' by Elder Dempster, and the 275 passengers booked for the ACCRA were reassured that the liner would sail from the Mersey on time, manned by the 101 European members of the crew.

The ACCRA working cargo in Liverpool docks

The Nigerians were demanding the removal from the ACCRA of the chief steward, second steward and chief storekeeper - all Europeans. They maintained that these three were responsible for discrimination between African and European crewmen over the distribution of food, drink and cigarettes. They claimed that the Europeans got better food; the beer for the African men was diluted, and that they were not allowed to buy certain brands of cigarettes! A spokeman for Elder Dempster said that the Europeans on board the ACCRA lived at a rather higher standard than did the African men, but that this would apply in any ship. He commented: "As regards the allegation that the beer is watered down, it's just unthinkable!"

The ACCRA sailed from Liverpool on 26th June 1959 with her passengers serving themselves to meals and making their own beds for the fourteen-day voyage. As they embarked they were told that they would each receive £1 a day as recompense for these inconveniences. The majority of the passengers regarded the whole affair as a joke, and there was only one cancellation. The striking Nigerian seamen were eventually flown back to Lagos in a chartered BOAC stratocruiser, paid for by Elder Dempster.

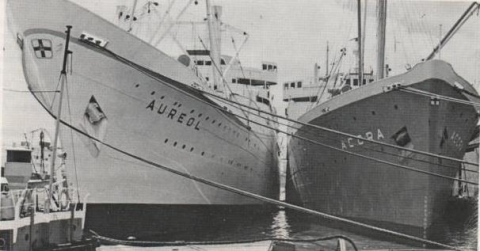

A photograph taken during the 1966 seamen's strike - the ACCRA and the AUREOL together at Liverpool.

The ACCRA's service in the Elder Dempster fleet was brief and on 8th November 1967, having completed 171 round voyages, she sailed from Liverpool for Cartagena, Spain, where she was demolished by J. Navarro Frances. Disturbed conditions in West Africa, which affected Elder Dempster's traditional trade, played a part in the relatively short career of the ACCRA.

The ACCRA being broken up at Cartagena, Spain.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

______________________________________________________________________________________________

A VOYAGE TO WEST AFRICA IN THE 'ACCRA'

by Fred Thompson

Liverpool, on a grey September day in 1952, did not present a particularly auspicious start to life in Africa. I had travelled from Euston on the boat train that, on arrival at Liverpool, had snaked its way across the streets, under the Overhead Railway, and alongside the Mersey to Riverside Station. I was allowed forty cubic feet of baggage as a newly-appointed Colonial Education Officer and I had two large wooden crates of household goods, a tin trunk that was meant to deter the voracious insects of forest or desert, and suitcases for my cabin. Each piece carried the Elder Dempster logo and a big letter 'T', this being my initial, to aid identification in the baggage hall. Customs and Immigration had to be cleared, currency regulations were strictly enforced, and only ten pounds sterling could be taken out of the country in cash. Baggage handlers were busy trundling trolleys on to the ship and I walked along a gangway into the entrance hall on 'B' deck. My previous voyage to sea had been in the cramped quarters of wartime troopers; this was different and it was First Class !

Cabin stewards came to meet passengers and I was taken in hand by a stocky Liverpudlian who led me to 'D' deck where I was to share a two-berth cabin. It was quite basic: there was a wash basin, two chairs, a tall cupboard and a storage space below two bunks, one of which was underneath a porthole. Bathrooms and toilets were situated nearby. My cabin mate was already installed; like me he was bound for Nigeria on first appointment as an education officer.

The ACCRA berthed on the Princes Landing Stage, Liverpool.

There was a little time to explore the ACCRA. The boat deck was damp and windswept. There was a generous allocation of space for public rooms which included a library, card room, smoke room and lounge. The entrance hall, still busy with embarking passengers, contained the purser's office, a shop, and hairdressing salons for both ladies and gentlemen.

Passengers were directed to the first-class dining saloon on 'E' deck to meet the Purser and make their table bookings for meals. The saloon was panelled in African hardwoods and the floor was covered with thick linoleum that could easily be washed down if need be, should spillages occur in rough weather. One end of the saloon was dominated by the captain's table, an elongated oval which seated nine guests. It was flanked by tables for senior officers. Crisp white table linen, sparkling cutlery and glassware shone in the subdued lighting. Tables seated four, six or eight passengers; senior colonial officers and company directors were guests at the captain's table and those of his senior officers. First-tour young men like myself were placed where the purser thought fit, usually close to the doors to and from the galley.

Prior to departure all passengers had been asked to provide to Elder Dempster details of rank, title, decorations and branch of service or company. Each of us received a passenger list and it was a formidable document. It included all the hierarchy of the colonial service; company directors of banks or the United Africa Company and bishops of African dioceses. There was a fair number of nursing sisters, women education officers and a handful of unaccompanied wives travelling out to join their husbands. There were very few children on board as it was government policy at that time to discourage parents from taking them to West Africa. Indeed, before the Second World War the reputation of the West Coast had been so bad that wives of colonial officers were allowed to accompany their husbands only with the greatest reluctance and had to pay their own passage. The development of anti-malerial prophylactics and the tremendous contribution made by wives in West Africa to the war effort had done much to relax the attitude of the British Government from the 1950s onwards.

The second-class passengers were accommodated aft in four-berth cabins. They had their own lounge and dining saloon, as well as a small area of deck space. The list included missionary families and a few Africans returning home from studies in Britain.

As the ACCRA was tied up at the Princes Landing Stage, Liverpool, dinner on the first night was informal. The ship's bars were closed and the open decks were deserted. Liverpool was wet. cold and dismal. However, the dining saloon was warm and inviting, and for those of us newly qualified from universities and used to the spartan diets of port-war Britain, the menu was staggering! Soup, hors d'oeuvres, fish, choice of entree, sweets, cheese, biscuits and coffee were served deftly and efficiently by stewards immaculate in bow ties and white jackets.

After dinner I wandered up to the boat deck to find a Force 10 gale howling up the Mersey. Departure was postponed for twenty-four hours. The bars remained closed and the crew was taking unexpected shore leave, but the passengers could not go ashore because of immigration regulations. Worse was the knowledge that Liverpool FC was playing at home, and our cabin steward went ashore to watch them.

The ACCRA sailing from Liverpool

The following morning, a Sunday, the ACCRA's engines were throbbing and she eased off the landing stage with the assistance of two tugs. At breakfast we could see the Irish Sea foaming past the portholes, and there was a pronounced motion on the ship, dip and roll, as the Welsh hills slipped past to port, and the dining saloon emptied rapidly as many passengers suddenly felt an aversion to bacon and eggs or grilled fresh kippers. Fiddles were rigged and the stewards swayed sure-footed with laden trays.

The Bay of Biscay was quite benign after the Irish Sea, and soon the dining saloon was full, the deck chairs were busy with passengers wrapped in rugs, whilst others were walking brisk circuits of the boat deck. The bars were open and everything was duty-free. Life was good!

The ACCRA outward bound in a rather choppy Crosby Channel in the Mersey Approaches

Shipboard routine was quickly established. Early morning tea with heavy white china bearing the Elder Dempster crest came on a silver tray with a selection of fruit, Breakfast was available from 08.00 until 09.30. The menu was huge: fruit juices, all cereals known to man, fresh fruit, fish such as grilled sole, bacon, eggs, mushroom and American hash with fried potatoes, bread in variety and Danish pastries.

Passengers staggered away to walk the deck, search out library books, plan deck games or just slump into deck chairs in sheltered corners. In the card room the bridge fanatics had established themselves. They played all morning, most afternoons and every evening. The children on board were actively discouraged from entering the room, and only the bar stewards were really welcome to replenish pink gins or brandy gngers at frequent intervals.

At around 10.30am hot bouillon was served; this would be replaced by ice cream once the ACCRA was in the tropics. At 11.30am the lounge bar and smoke room bars opened; the beer was popular but seasoned colonial officers preferred a pink gin! Luncheon was served from 12.30.

After lunch was a quiet time; many passengers took a siesta either in their cabins or on deck where the weather was becoming ever warmer. At 3.30pm tea - cucumber and salmon sandwiches with cream cakes to follow - would be served by stewards or was available on a 'help yourself' basis in the lounge.

Dinner was now a formal occasion for all on the captain's table and those of the senior officers. The gentlemen wore stiff shirts, bow ties and mess jackets and the ladies were in long frocks, some with elbow-length gloves.

The ACCRA's first port of call was Las Palmas in the Canaries. This was anticipated with great excitement for, in 1952, it was a 'free' port. Goods not available in England, or available but subject to heavy import duty, were to be had virtually 'at cost' in Las Palmas. Our stay would be short because of the late departure from Liverpool. Many local traders came on board and set out their wares on the boat deck.

As the passengers returned to the ACCRA for an evening departure, they found changes much in evidence. The swimming pool had been filled; the ship's officers had exchanged blue serge for white drill shirts, shorts and long white socks. We were now only a few days from Africa, and flying fish as well as dolphins reminded us that we were in tropical waters.

The ACCRA's dawn arrival at Freetown evoked memories of my wartime visit some nine years earlier. On that occasion the harbour was filled with a south- bound convoy, and two frigates rushed out into the Atlantic to ambush a wolf- pack that had shadowed us for much of the voyage. Then, as now, the bumboats came out to meet us. There was no deep-sea wharf at Freetown in 1952, so lighters came out for the cargo, and disembarking passengers went ashore by launch.

Once the ACCRA was underway again, news came that the onward postings had been received. Colonial officers going to the Gold Coast or to Nigeria had to wait until the ship had left Freetown to learn of their final desrinations. All postings were advised to the ship in Morse Code and against my name I found 'Kathina'. I looked at the map near the notice board and could not find it. An old hand soon put me right: "That should be Katsina, the radio officer got his morse wrong and read four dots instead of three. I hope you play polo - the Emir is dead keen!"

The voyage continued around the bulge of Africa and into the Bight of Benin. The ACCRA was never far off the land, and by day the high cumulus could be seen building up over the coast, heralding the heavy rain of an equatorial afternoon. Takoradi was our next call; a new port built to serve what was then the Gold Coast, within a few years to be Ghana. Here there was a deep water quay with berths for six vessels; yet only a few years before Elder Dempster ships had anchored offshore and surfboats, paddled by Kroo boys, had carried passengers and cargo ashore through the surf. It was the Kroo boys' proud boast that the passengers were safely landed without even a splash on their toes!

The ACCRA could carry 150 deck passengers and a large number boarded at Takoradi. Many were semi-itinerant labour, seeking work in the boom city of Lagos. Some came with their families, laden with cooking pots, charcoal, yams and bedding rolls. The forward deck was a mass of busy, vociferous, colouful people. Working space was restricted and this did little to improve the tempers of officers and deckhands working the ship.

The ACCRA approaching her berth at Lagos

The following day found the ACCRA steaming slowly into the harbour at Lagos. To starboard was Lagos Island, the old colonial capital. Apapa Wharf was on the port side where the ACCRA would berth. This was the end of the voyage with customs and immigration formalities to be cleared. In the early 1950s these presented no great problems, although old hands maintained that to wear a King's College Lagos tie ensured a speedy passage through, as all the shore officials claimd to have relatives at K.C. !

It was all exciting; Lagos was noisy and noisome, colouful and brash, and already alive with nationalism, although the goal was still nine years away. I spent one night in the house of the Inspector General of Education. My onward journey north was to be by train, but the track had been washed out, so I spent the next fortnight fuming in the Ikoyi Rest House, a former RAF camp that had little to recommend it. It was ill lit, damp, humid, infested with mosquitoes by night and lacking basic facilities. It was an inauspicious beginning to what became, in the end, five very happy years up country in Katsina, where I never played polo but enjoyed by cricket! ⊗⊗⊗⊗⊗⊗

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

|